The new Anti-Child Labour law may have come to the rescue of many underage working children in the country but as the media has been constantly reporting, the law has made survival more difficult for some others.

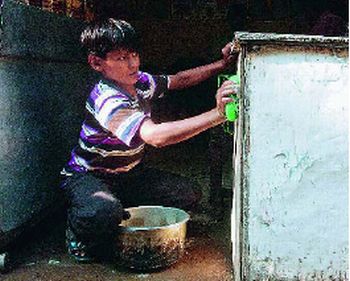

For instance, 12-year-old Birendra Kumar is orphaned and already on his second job.

He is the face of the other side of the Anti-Child Labour law, a side that makes more vulnerable exactly those it is supposed to protect.

Birendra's new job is at a Patna dhaba - washing dishes and serving tea.

He lost his first job which was in a cloth showroom as the owner of the shop didn't want to keep him once the law came into force.

"I used to work in a cloth store and used to earn Rs 1000 a month. I lost that job and now I work at a tea stall,” says Birendra.

His new job pays him half of what he used to earn earlier, only Rs 500. With that, he not only has to fend for himself but he has to take care of his four-year-old sister as well.

"We don’t have parents,” says Birendra’s sister, Chutki.

In eyes of law, Birendra is still an offender and so is his employer but he has to continue working to earn money that keeps him and his sister alive.

He knows he is defying a law that has been much talked about but he also realizes that he has little choice.

"We are in dire straits. We want to go to school but we don’t have the money,” he says.

Locals have little to offer but pity for the children. “He is the only earning member of the family. They will starve if he stops working,” says a local resident, Ranjeet Kumar.

There are thousands of Birendras and Chutkis for whom this law is not a boon and even those who are in the crusade of enforcing the law hardly look beyond the rule books.

So this is a request to the Lawmakers please think twice before imposing any law on society. I am not a supporter of child labour but before imposing any law we should provide an environment which could preserve that law. Our society still not provided any other alternative to those poor children so how could we expect anything good?